What Are We Preserving?

But as we have seen, the promise of these façades was never intended

as a true offer. To the workers, forced to enter through their monumental

portals into a world without toilets or other middle class niceties, their

grandiose statement was always plainly false. For the middle class public,

it only now appears incongruous, as they pass through the entrances for

the first time. In fact, the true historic nature of the structures is

clearly expressed by the incongruity between exterior and interior. To

the extent that the interiors are now to be bowdlerized and polished,

that character defining relationship is compromised, and the historic

expression of the structure is concealed.

Pier One has been converted to the new headquarters for the Port of San

Francisco. The rehabilitation was awarded federal tax credits, was recognized

by the AIA and the Urban Land Institute, and has generally been applauded

among preservationists. Yet the project not only destroyed the important

sense of contrast between façade and interior, it eliminated the

separate identities of pier shed and bulkhead building. Any sense of the

historic work environment of the pier is now completely gone. This loss

was allowed because the National Register nomination made no case for

historic significance based on the labor history of the property. The

officially recognized history, in other words, is blind to any meaningful

association with the work that gave form to the structures. Another project

already approved for Pier Three actually includes the demolition of the

remaining portion of the pier shed, and exhibits the same dismissal of

the historic importance of the labor, and its social context, for which

the buildings were created.

Although usually not recognized, this problem lurks in the preservation

of many historic work sites, for spatial practices are seldom neutral—and

historic preservation is a type of spatial practice. The problem is particularly

troublesome where questions of class are involved, as here, because class

remains one of the least understood social constructs in American culture.

But most preservationists come from the middle class. As a result, historical

class associations are seldom perceived during rehabilitation projects,

so their physical manifestations, often seen as crude, unpleasant, or

even frightening in middle class eyes, are easily destroyed.

On the San Francisco waterfront, the destruction of working class memory

includes also the removal of memorials, such as the Andrew Furuseth bust

dedicated in 1941 in front of the Ferry Building, honoring the founder

of the Sailor’s Union of the Pacific; the SS Baton Rouge Victory

memorial to merchant seamen killed in Vietnam, now displaced by Cupid’s

Span; and the sale for scrap of two National Register eligible pile driving

barges, the last of their kind anywhere and rich repositories of the history

of the working people who actually constructed the waterfront currently

being reappropriated.

What can be done? Preservationists must come to see that their own cultural

vision interferes with their fully understanding workplace structures.

When arguments such as those in this paper are presented, a common response

from professionals is that they do not have the expertise to analyze the

resources in this way. Although not as readily stated, there is also an

assumption that it just isn’t important enough to do so. It is certainly

true that most preservation professionals do not have the needed expertise.

The obvious answer is to partner with those who do. This must include

not only labor and social historians, but whenever possible, people who

actually worked in the structures during their period of significance.

As for the question of the importance of this historic context; there

should be a beginning presumption that the program for the building included

the organization and command of the work it contained. The early factory

system itself was created in order to bring formerly dispersed workers

together under the greater direction of the employer, thus creating the

need for a new building type. Every industrial workplace, from textile

mills to office buildings, descends from that lineage. That is—every

industrial workplace was an instrument of social control. Any analysis

of a workplace that does not recognize this is seriously flawed.

Most importantly for preservation, without this understanding, it is not

possible to identify character defining features conclusively, and therefore

not possible to protect the integrity of the structure. In order to do

a proper job of rehabilitation, and not to be complicit in the eradication

of working class history, preservation must come to see that it is necessary

to partner not only with different people—but with different understandings.

|

|

| Pier 1 exterior | |

|

|

| Above and below: Pier 1 interiors after "rehabilitation" | |

|

|

|

|

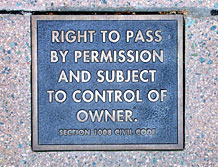

| "Waterfront plaque," foot of Folsom Street, site of founding of Sailors Union of the Pacific, oldest maritime union in the country. | |

|

|

| "Cupid's Bow" displaced 1993 S.S. Baton Rouge Victory monument commemorating merchant seamen wartime casualties. |